Szabo’s Law, Crypto-Libertarianism, Techno-Utopias, & Decentralized Governance Part 1

Mar 14, 2019, 10:40pm

A look at decentralized governance from Szabo's law to Bruce Schneier's crypto-economy critique and Vlad Zamfir's thoughts on crypto governance.

This is part one of a two-part piece on “Szabo’s law” and competing notions of the sovereignty of code in decentralized governance models.

Knowledge so conceived is not a series of self-consistent theories that converges towards an ideal view; it is not a gradual approach to the truth. It is rather an ever increasing ocean of mutually incompatible alternatives, each single theory, each fairy-tale, each myth that is part of the collection forcing the others into greater articulation and all of them contributing, via this process of competition, to the development of our consciousness. Nothing is ever settled, no view can ever be omitted from a comprehensive account.

— Paul Feyerabend, “Against Method”

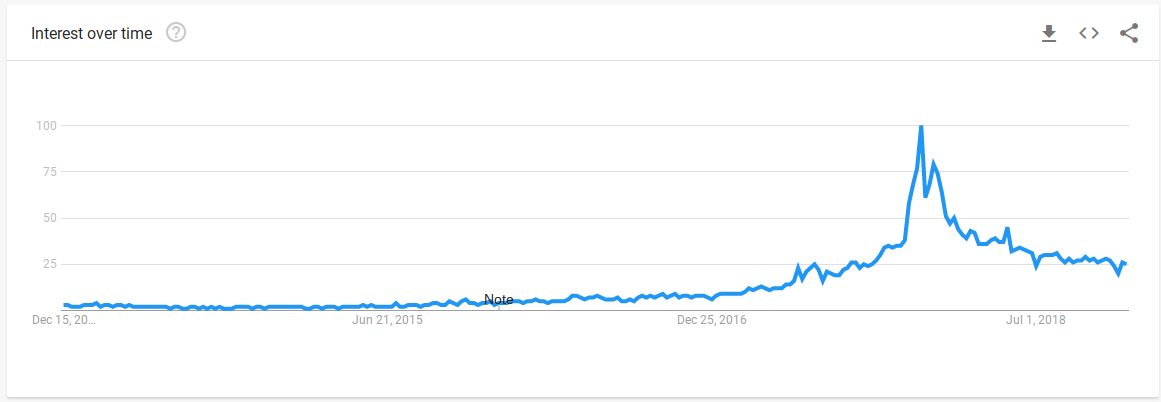

Renowned cryptographer and security expert Bruce Schneier recently published an essay on blockchains and trust which reads like a sobering pinch back to the basic facts of reality and a dose of much needed (if not a bit overdue) antidote to the overwhelming hype surrounding blockchains and the promise of cryptocurrency over the past couple of years. Not too long before that Ethereum’s Vlad Zamfir wrote a blog post launching similar critique against the idea of passive "code is law" governance seeking to replace the agora and political processes of human decision-making with autonomous instances of pre-programmed self-executing recipes and feedback mechanisms on top of a protocol that is “set in stone”.

As a reminder, Ethereum early on in its inception split into two separate chains after the notorious DAO hack. One is the Ethereum we know as the mainstream one and the other (the original, non-forked chain that stood up for immutability as a foundational cornerstone) is Ethereum Classic. The divergent philosophies of the two are expressed in Zamfir’s opinion piece (i.e., ETC more closely aligns with the "code is law" rationale that also seemingly governs Bitcoin core, while Ethereum gives precedence to the “world computer” programme and takes a more “move fast and break things” approach to innovation).

As a technological medium in a way co-extensive with our central nervous system, the hyper-connected domain of cyberspace has always been, due to its nature, problematic to integrate within existing legal frameworks and jurisdictions, as well as slippery when it comes to negotiating agreements and rules governing relationships and behaviors of all the various involved entities and actors in this essentially open, rhizomatic and smooth (to use the Deleuzian vocabulary) space. In a recent blog post of his, “Cybersecurity for the Public Interest”, Schneier says:

We need policymakers who understand technology, but we also need cybersecurity technologists who understand — and are involved in — policy. We need public-interest technologists.

The open access to knowledge and freedom of association that defines the Internet naturally accelerates the pace of innovation, making the next step further in affording access to the means of production with the advent of things like 3D printing (making it possible to download a design and print it out), synthetic biology and DIY bioengineering (also known as “biohacking”). And the global nature of these phenomena complicates the job of governments and regulatory bodies, as they often even lack the adequate terms, competence, language or legal framework for addressing the issues they face.

“May thou come to the attention of those in authority.”

— Chinese curse

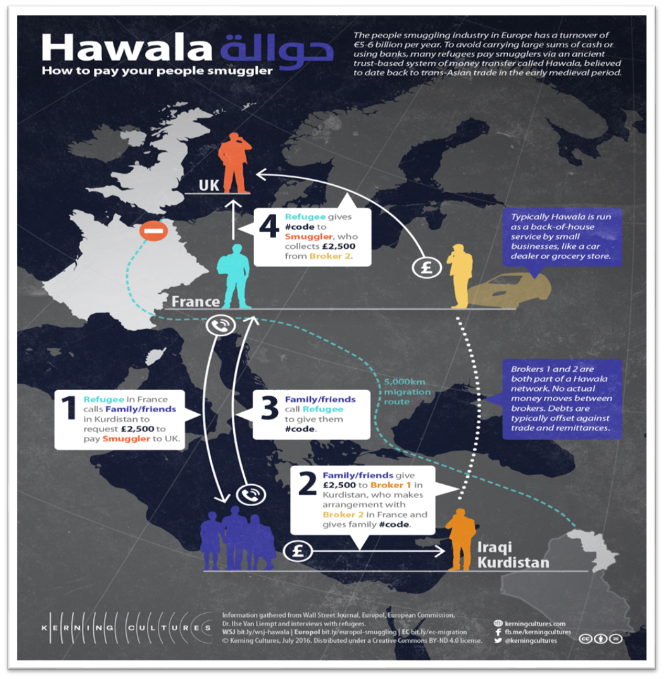

The Internet is today even considered a fifth operational domain of warfare alongside the traditional domains of land, sea, air, and space. Bitcoin introduced a sort of rogue network for transferring of value on top of the Internet, a kind of unregulated non-state crypto-hawala which, in the first few years of its existence, was mostly associated with drug money and fraud, or seen as a money laundering instrument (or, at one point as means to circumvent regulation and siphon capital out of China).

Obviously, as a technologically complex society we function as actor-networks within the fabric of larger socio-technical systems, but technology as such, in itself, is blind, deaf and dumb (“value agnostic”). There’s always human operators and administrating bureaucracies, overlapping complex adaptive systems of various kinds and loosely coupled sub-systems forming temporary ad hoc assemblies of actor-networks for various purposes.

The nihilistic techno-fetishism of ontologically privileging technology over all else, which wants to deliver us from ourselves and code us out of existence by delegating decision-making to blind automatons and what not is a fairly fringe phenomenon that couldn’t possibly be taken seriously.

American-style libertarians abound on the Internet. Computer programmers are highly susceptible to the just world fallacy (that their economic good fortune is the product of virtue rather than circumstance) and the fallacy of transferable expertise (that being competent in one field means they’re competent in others). Silicon Valley has always been a cross of the hippie counterculture and Ayn Rand-based libertarianism (this cross being termed the “Californian ideology”).

“Cyberlibertarianism” is the academic term for the early Internet strain of this ideology. Technological expertise is presumed to trump all other forms of expertise, e.g., economics or finance, let alone softer sciences.

— David Gerard – Attack of the 50 Foot Blockchain: Bitcoin, Blockchain, Ethereum & Smart Contracts (2017)

But while collectively run and managed crypto-currency networks may have been originally conceived in the post-2008 climate and the background of the cypherpunk movement and radical crypto-libertarianism (or the “Californian ideology”), open source ideas (or just ideas in general) don’t swear loyalty or pledge allegiance to any one specific subculture, ideology or world-view.

Security in Distributed Public Crypto-Ledgers

A well-known figure in the space, Nick Szabo is a cryptographer, computer scientist and legal scholar coming from that 90’s cypherpunk culture and known for his research in digital contracts and digital currency. His design for a decentralized digital currency, “bit gold”, has been called a direct precursor of Bitcoin (despite “bit gold” never having been implemented). He coined the very phrase “smart contracts” in the mid-’90s, with the intention of bringing what he calls the “highly evolved practices of contract law and practice to the design of electronic commerce protocols between strangers on the Internet”. He differentiated between “wet code”, or human language and expression (ambiguous and imprecise, with semantic meanings shifting and subject to interpretation depending on the context) and “dry code”, or machine code – the binary machine logic and circuitry upon which computers operate and execute pre-programmed instructions.

Contrary to Szabo’s libertarian-leaning and, according to Zamfir, “aggressive legal posture” and “anti-social behavior”, Vlad sees distributed crypto-institutions not as something so fundamentally or radically different from the already instituted ones, but rather an attempt and an opportunity to re-build institutions anew, bottom-up and do our best to prevent them from becoming corrupted from within or captured by interests that don’t align with those of the communities that have worked to build them or the public whose confidence they’re come to be entrusted with. And to that end, we mustn’t hope to replace the political with mathematics and claim to be exempt from politics and responsibility, but on the contrary, we should rather take full advantage of our new-found autonomy.

As a security professional used to dealing with and estimating risk and the trade-offs involved in security engineering, Schneier’s conservative position is even more critical of blockchained crypto-economies, but also pointing out what had and should have been eye-pokingly obvious all along: no blockchain-based crypto-currency is a self-contained, independent system that can be considered in isolation or as genuinely trustless (Szabo emphasizes that it is a matter of trust minimization, not trustlessness). One must still trust the underlying technology, the interfacing front-ends, and applications, etc.

Additionally, software is never bug-free, exploitable vulnerabilities are a fact of life and there’s never a guarantee that what seems to work today will not be obsolete just a year later – therefore, things like “smart contracts” and dApps, irreversible and immutable by definition and designed to secure and handle large sums of value, should be scrutinized much more carefully by many more eyes from many different angles of expertise and kinds of exposure. Hopefully, in the Web 3.0 we’ll get to collectively learn the lessons we skipped in the Web 2.0 (which, also, was born from an initial tech bubble).

And while the state government with its institutions and agencies have too often proven inefficient, cumbersome, incompetent, negligent, and even cynical in how they fulfill their supposed responsibilities and manage public interests, just wishing that they would go away and thereby pave the way for something better, presumed on the basis of beliefs, wishful thinking, ideologically grounded assumptions and ideas about social order do not suffice (as cliodynamics scholar Peter Turchin also recently argued on the subject with well-known anarchist activist and anthropologist David Graeber). According to Schneier, it is not a matter of whether or not we need regulation, but rather a matter of responsible, “smart” regulation (one understanding of the nature and gravity of the situation) versus an ill-informed and not so smart one.

And while some may read this as signaling the failed promise of blockchains and distributed crypto-ledgers, open economies, and legitimate self-governing institutions, this, I think, is far from the case (and even on the contrary). We’re all still just as free to build, design, experiment, and group in various forms of decentralized organizations, meaningfully contributing and carving our own futures and outcomes we choose to collectively pull towards. But we can only proceed so with the necessary understanding, thoughtful caution, and epistemic humility.

Bruce Schneier: Blockchain and Trust. A Step Back and Reminding Ourselves of the Obvious.

Schneier is a well-known security expert and cryptographer who has been involved in the creation of many cryptographic algorithms, hash functions (such as Skein) and ciphers (Blowfish, Twofish, etc.) and has authored a number of popular books including “Applied Cryptography” (a handbook of cryptographic principles, primitives, methods and algorithms), “Liars and Outliers: Enabling the Trust that Society Needs to Thrive” (which I personally highly recommend as relevant to the subject at hand), “Data and Goliath” and, most recently, “Click Here to Kill Everybody”.

In his recent essay (which was also published in Wired.com), Schneier warns about the misplaced trust in blockchains and the semantic abuse of marketing something as trustless. In the beginning of “Liars and Outliers” Schneier highlights the fundamental role of trust in keeping society as such together (places where for some reason or another no meaningful or lasting forms of trust-based cooperation are able to form, cliodynamics researcher Peter Turchin refers to as asabiyyah black holes, giving as examples places like Somalia, Afghanistan, etc.).

In this post-2008 day and age, of fake news and alternative facts, superficiality and low attention span, shamelessness and widespread fraud (a kind of ubiquitous cynicism usually symptomatic of the final days preceding the collapse of an empire) — a time of rapid loss of confidence in institutions and politics and of form trumping content, it only makes sense that some sort of trustlessness, as a shift away from trust in the hopelessly corrupt and unpredictable, self-interested human nature toward the reliably predictable and value-neutral machinic one, of techne and precise mathematics, might seem appealing on the surface.

This is especially true given the how Western civilization has privileged science over other forms of knowledge for as long as it has (even raising it as an ideology itself) and how it has comfortably assumed that technological innovation will be the eventual salvation and solution to all problems (something we should perhaps also thank Keynes for). Alas, as Schneier points out, things are never as straightforward as our theoretical models when it comes to the messy world and how things actually work out in reality.

The circumvention of trust is a great promise, but it’s just not true. Yes, bitcoin eliminates certain trusted intermediaries that are inherent in other payment systems like credit cards. But you still have to trust bitcoin — and everything about it.

Schneier goes on to give a proper definition of blockchain:

First, a caveat. By blockchain, I mean something very specific: the data structures and protocols that make up a public blockchain. These have three essential elements. The first is a distributed (as in multiple copies) but centralized (as in there’s only one) ledger, which is a way of recording what happened and in what order. This ledger is public, meaning that anyone can read it, and immutable, meaning that no one can change what happened in the past.

The second element is the consensus algorithm, which is a way to ensure all the copies of the ledger are the same. This is generally called mining; a critical part of the system is that anyone can participate. It is also distributed, meaning that you don’t have to trust any particular node in the consensus network. It can also be extremely expensive, both in data storage and in the energy required to maintain it. Bitcoin has the most expensive consensus algorithm the world has ever seen, by far.

Finally, the third element is the currency. This is some sort of digital token that has value and is publicly traded. Currency is a necessary element of a blockchain to align the incentives of everyone involved. Transactions involving these tokens are stored on the ledger.

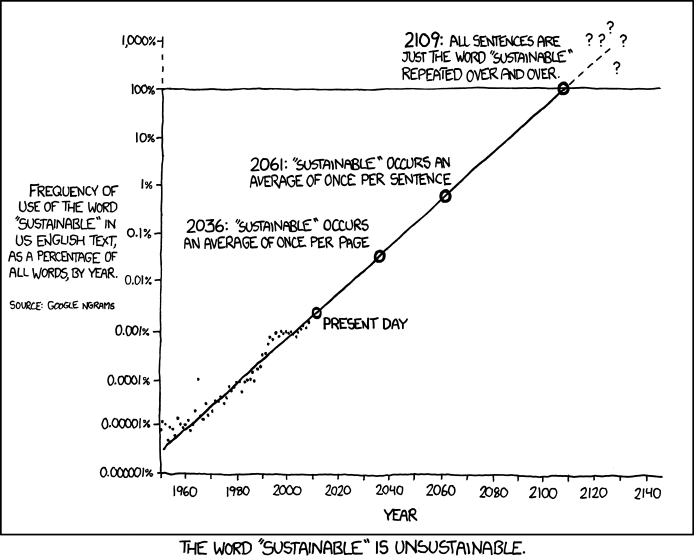

So, not every possible distributed ledger technology (DLT) or shared database is necessarily a blockchain. But the term was picked up and adopted for mostly marketing purposes (as was the term “crypto” likewise appropriated), becoming part of the common pixie dust buzzwordery still often employed.

Blockchain enables this sort of trust: We don’t know any bitcoin miners, for example, but we trust that they will follow the mining protocol and make the whole system work.

Most blockchain enthusiasts have a unnaturally narrow definition of trust. They’re fond of catchphrases like “in code we trust,” “in math we trust,” and “in crypto we trust.” This is trust as verification. But verification isn’t the same as trust.

In 2012, I wrote a book about trust and security, Liars and Outliers. In it, I listed four very general systems our species uses to incentivize trustworthy behavior. The first two are morals and reputation. The problem is that they scale only to a certain population size. Primitive systems were good enough for small communities, but larger communities required delegation, and more formalism.

The third is institutions. Institutions have rules and laws that induce people to behave according to the group norm, imposing sanctions on those who do not. In a sense, laws formalize reputation. Finally, the fourth is security systems. These are the wide varieties of security technologies we employ: door locks and tall fences, alarm systems and guards, forensics and audit systems, and so on.

The fourth category, the security component, is no doubt critically important in distributed crypto-economies for obvious reasons that have been demonstrated time and again in real life over the past decade. In that regard, formal methods, verifications, and mathematical proofs have lately entered the domain of smart contracts (approaches most often employed in the context of mission-critical systems, such as space shuttles and nuclear programs) – a newly forming paradigm and category of programming languages.

Organizations like the IOTA foundation seem to have taken an altogether different approach to the matter (the possibility of substituting pseudo-random complexity with more computationally simple, truly random one), but up until now the prevailing philosophy has been that of Occam’s razor (a problem-solving principle that states that simpler solutions with fewer assumptions are more likely to be correct than complex ones) and the KISS principle (Keep It Simple Stupid, a guiding design principle in the UNIX philosophy) of maintaining a degree of manageable simplicity over how we design our systems. But there are many instances in which this may no longer apply so, as innumerable variables loom up in the process of rapid technological acceleration (Paul Virilio coined the term ‘dromology’ to mean the logic of speed that is the foundation of technological society).

What blockchain does is shift some of the trust in people and institutions to trust in technology. You need to trust the cryptography, the protocols, the software, the computers and the network. And you need to trust them absolutely, because they’re often single points of failure.

When that trust turns out to be misplaced, there is no recourse. If your Bitcoin exchange gets hacked, you lose all of your money. If your Bitcoin wallet gets hacked, you lose all of your money. If you forget your login credentials, you lose all of your money. If there’s a bug in the code of your smart contract, you lose all of your money. If someone successfully hacks the blockchain security, you lose all of your money. In many ways, trusting technology is harder than trusting people. Would you rather trust a human legal system or the details of some computer code you don’t have the expertise to audit?

Blockchain doesn’t eliminate the need to trust human institutions. There will always be a big gap that can’t be addressed by technology alone. People still need to be in charge, and there is always a need for governance outside the system. This is obvious in the ongoing debate about changing the Bitcoin block size, or in fixing the DAO attack against Ethereum. There’s always a need to override the rules, and there’s always a need for the ability to make permanent rules changes. As long as hard forks are a possibility — that’s when the people in charge of a blockchain step outside the system to change it — people will need to be in charge.

Any blockchain system will have to coexist with other, more conventional systems. Modern banking, for example, is designed to be reversible. Bitcoin is not. That makes it hard to make the two compatible, and the result is often an insecurity. Steve Wozniak was scammed out of $70K in Bitcoin because he forgot this.

This paragraph captures the very essence of the problem we face and the implicit paradoxes and limitations in trying to deal with it by means of any “final” solution or a single “correct” prescription. But it is worth remarking that we have been overwhelmed with technologies that we have very little to no understanding of over the last half a century of our existence as a human species. And any technological revolution always carries with it its implicit, unpredictable, and unintended consequences — or even implicit genocides, some might say (a subject Marshall McLuhan dedicated his life’s work to exploring and trying to effectively explain and demonstrate). One just needs look back at the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century (which nearly wiped out the lower classes in the process of industrialization, as it subsequently wrecked the same elsewhere).

Moreover, in any distributed trust system, there are backdoor methods for centralization to creep back in. With bitcoin, there are only a few miners of consequence. There’s one company that provides most of the mining hardware. There are only a few dominant exchanges. To the extent that most people interact with bitcoin, it is through these centralized systems. This also allows for attacks against blockchain-based systems.

Centralized exchanges (since MtGox, which itself had, astonishingly, been casually written in PHP in the course of a few days) have always been the most vulnerable point when talking crypto-currencies, but they are far from the only issue of concern. Evading capture, as well as security, are dynamic processes of continuous, active engagement – there is no point of final arrival or a one-size-fits-all recipe to implement so we can all finally just relax and not need to know much of anything. Quite on the contrary. Doing away with or minimizing the role of states, governments or banks means accepting more personal responsibility in assuming their role ourselves.

Do you need a public blockchain? The answer is almost certainly no. A blockchain probably doesn’t solve the security problems you think it solves. The security problems it solves are probably not the ones you have. (Manipulating audit data is probably not your major security risk.) A false trust in blockchain can itself be a security risk. The inefficiencies, especially in scaling, are probably not worth it. I have looked at many blockchain applications, and all of them could achieve the same security properties without using a blockchain — of course, then they wouldn’t have the cool name.

I myself am not sure if I entirely agree with the above. Public blockchains – perhaps really not so much (though they undoubtedly are useful in some specific, limited set of circumstances and use cases). But distributed crypto-economies and shared ledgers as a decentralizing technology and a means for global coordination and cooperation certainly do bring much hope on the horizon. But we must be honest and come to terms with the obvious – global consensus does not and cannot scale on the level of a world currency (and neither should it). And not all decisions are binary, deterministic either/or’s – more often there’s a grey area of an in-between spectrum we seem to often forget about.

To answer the question of whether the blockchain is needed, ask yourself: Does the blockchain change the system of trust in any meaningful way, or just shift it around? Does it just try to replace trust with verification? Does it strengthen existing trust relationships, or try to go against them? How can trust be abused in the new system, and is this better or worse than the potential abuses in the old system? And lastly: What would your system look like if you didn’t use blockchain at all?

Schneier’s recent talk after the publication of his latest book, “Click Here to Kill Everybody: Security and Survival in a Hyper-connected World”.

My own response to this last argument is that distributed crypto networks that secure and circulate some form of value, as defined by the economy of its participating actors, constitutes the stage for cultivating and organizing the potential of powerful forces (of actors, for instance, that couldn’t have otherwise previously formed meaningful networked alliances or afforded to gear economic incentives towards some desired outcome or shared goal). Regardless of the fact that while in theory there is no difference between theory and practice, in practice, theory often gets turned on its head. Nonetheless, institutional technology may not necessarily mean state technology – not all human institutions are state governed, but rather most human institutions are driven by the values they are set up to uphold, represent, and guard. And these values are not necessarily measured in what money can buy.

Vlad Zamfir: Against Szabo’s Law, For A New Crypto-Legal System. Putting the Doctrine of Immutability in Question.

A strong doctrine of immutability minimizes the control of human whim over our money.

Crypto governance encompasses polemics and debates over how we coordinate to make decisions on changing the rules of the protocol, which may include anything from minor upgrades to changing consensus algorithms to allocating block rewards and managing commonly-held treasury capital to anything else beyond and in between. It involves many stakeholder groups such as node operators, network providers (miners or validators), core developers, end-users, speculators, and exchanges, to name a few. These are diverse groups with varying incentives that sometimes collude and come in conflict with each other. For example, the Bitcoin issues of node operators wanting to keep block-size low to reduce the costs of running a full node come in conflict with miners who have incentives to increase the block-size to include more transactions in a block and thus harvest more transaction fees (see, Bitcoin SV, Craig Wright and Calvin Ayre).

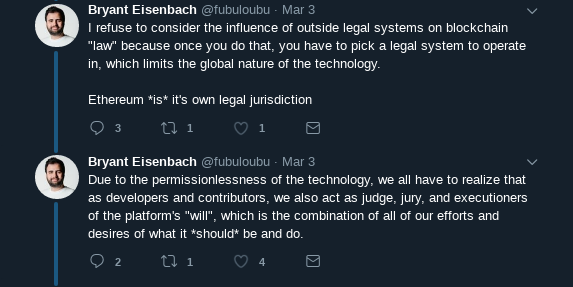

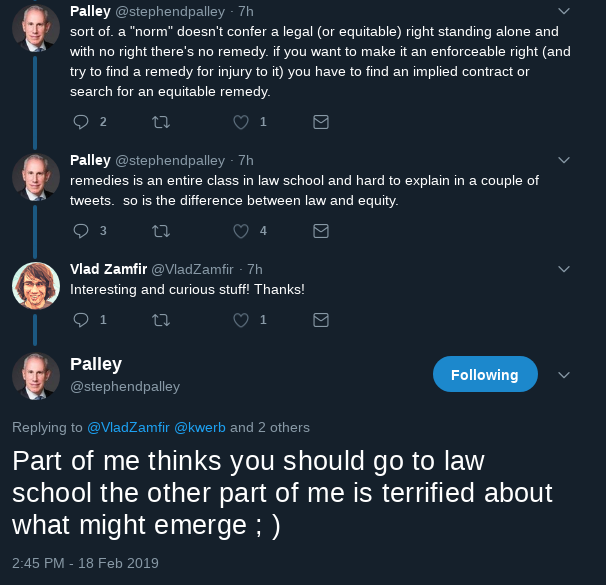

Legal systems as such can be loosely defined as protocols, formal guidelines and procedural frameworks for the management of disputes and in his blog post, Zamfir goes on to identify three generally accepted laws and guiding operative principles of crypto-systems law as applied today in dispute management and blockchain governance. The first law is to not break the protocol (e.g., disputes are never resolved by the introduction of critical bugs or by launching certain attacks just because we can). The second law is to do with keeping things overall legal in the sense of not explicitly being illegal in the terms of the jurisdictions they happen to find themselves at and operate in (this often surfaces in issues that are extremely difficult to resolve, since different jurisdictions do not always cooperate in these matters and some have even taken advantage of this fact to further weaponize and militarize cyberspace).

However, the third law, which he refers to as Szabo’s law prohibits the implementation of changes to protocol for any other reason other than technical maintenance. And while the first two laws are fairly self-explanatory and self-evident, the third one has important implications.

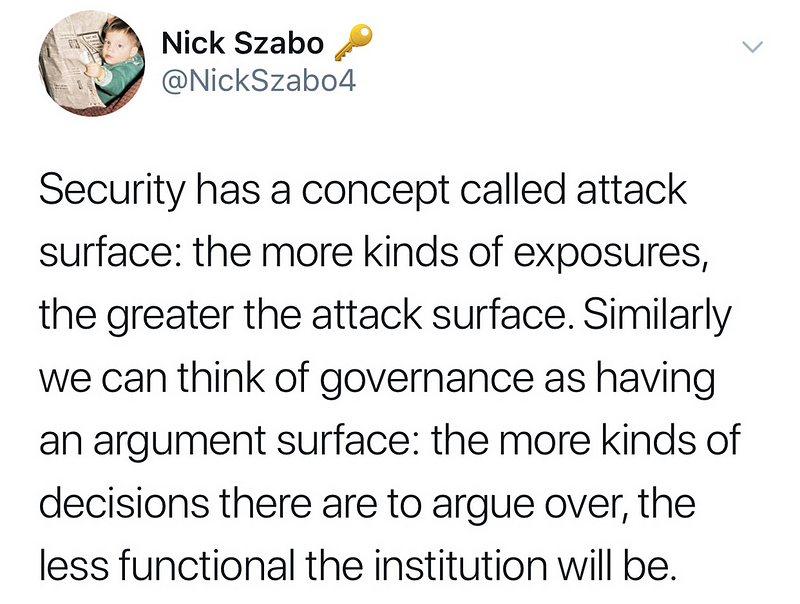

Nick Szabo has popularized (and legalized) his law in a few ways:

1. By popularizing autonomous software in the crypto legal form of smart contracts

2. By arguing that the minimization of responsibility for developers isolates them from legal risk

3. By arguing that crypto legal systems with Szabo’s law are more socially scalable than systems with more legal and political power.

Nick’s crypto law is responsible for a lot of the talk (and law) around the blockchain being immutable, and needing to remain immutable, and has justified decisions by developers to refuse to make changes to the blockchain protocol when they are engaged in blockchain governance disputes (for example in the Bitcoin block size debate). The DAO hard fork was a clear violation of Szabo’s Law, and it offended Nick enough that he disowned Ethereum in favor of Ethereum Classic. But Szabo’s law has been cited in Ethereum blockchain governance disputes after the DAO hard fork (specifically, in the still-unresolved stuck funds dispute). Indeed, Nick Szabo’s law is often cited by core developers to justify their choices in blockchain governance disputes. Szabo’s law is therefore crypto law.

There’s a thin line here, and as David Gerard points out in the citation at the beginning, there is the side-effect of nerdification which tends to produce the naive belief that “technological expertise is presumed to trump all other forms of expertise, e.g., economics or finance, let alone softer sciences.” Also, in the case of the second crypto law pointed out, we should remember that Bitcoin and crypto-currency had for a long while in its earlier days been used mostly as means for conducting illegal business on black markets (an era characterized by things like the Darknet, the controversial Silk Road and similar Tor-routed markets for illegal goods that transact in Bitcoin because of it being pseudonymous and more difficult to trace to any one specific person) and for money laundered from fraudulent and other more or less illegal activities.

Nick Szabo forged a crypto law and popularized a legal theory that created software that is way more autonomous than society is capable of creating without the use of law.

In truly revolutionary cypher-legal-punk style, he created autonomous software with a crypto law and a legal theory that is profoundly and radically anti-legal and anti-political.

That the political and legal climate of the world was ready to embrace a legal theory and a law that is premised on the idea that legal and political processes are unworkable and need to be ruthlessly minimized, that software needs to be autonomous to be trusted is absolutely astonishing.

What a time to be alive!

In a way, perhaps envisioning a world somewhat reminiscent of William Gibson‘s techno-prophecy described in Neuromancer and the dystopic Sprawl trilogy (Gibson considered the father of the cyberpunk literary genre of speculative fiction – not to be confused with “cypherpunk”, though there’s an association). A world in which corporations, organized crime syndicates, governments and clandestine networks of evolved, autonomous systems and distributed intelligence have colonized the world and interplay in strange and unpredictable ways, while biological and human life has grown replicable, commodified and therefore just as artificial and less intrinsically valuable. A grim dystopia beginning with the memorable line: “The sky above the port was the color of a television tuned to a dead channel.” Interestingly, Gibson is said to have coined the term cyberspace and prophesized the significance of the age of the Internet way back in the early 1980s.

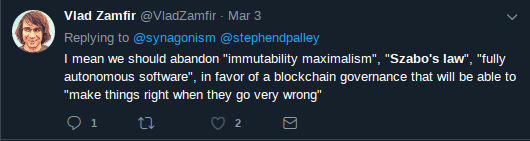

But back to Szabo’s law. Zamfir goes on to argue four points again Szabo’s law:

1. Szabo’s Law breaks Crypto Law #2 (Keep Crypto Law Legal)

2. Szabo’s Law is politically loaded, not politically minimal, apolitical or anti-political

3. Szabo’s Law has an insecure and aggressive legal posture

4. Szabo’s Law is not a part of the most socially scalable crypto legal system

All four points are argued at length in the blog posts, although they are fairly obvious and don’t really require any technical expertise to immediately grasp. As I have emphasized on other occasions elsewhere, we should think of crypto-currency and Bitcoin and Ethereum, etc. as much as a technical experiment, as also (or perhaps even more so) as a social one.

Bruno Latour and his Actor-Network Theory (ANT) stress the fact that the social is neither exclusively made up of humans, or people, the institutions they set up, their cultural foundations, etc. nor strictly quantitative, statistical or lending itself to being reduced to single-dimensional analysis (e.g., as homo economicus, a calculating agent motivated solely and exclusively by self-interested accumulation of capital), but rather constitutes an ongoing process of networked relations, alliances and arrangements between things, both human and non-human, material and semiotic (e.g., technology, microbiology, electrochemistry, seasonal climate, and temperature fluctuations, applied formulas and instruments of measure, etc.), which together form the complex socio-technical noosphere we occupy (Latour himself mentions he would have called his approach rhizome-actant ontology).

Obviously, the human element cannot be fully replaced by a Leviathan of algorithmically enforced “law”, since machines merely execute the simple logic of some given conditional instructions and maintain the looping inertia of the program they’re set to run. Instead, autonomous feedback mechanisms and established protocols serve to reliably mediate formally negotiated relationships between actors that voluntarily enter into such agreements, the outcomes of which get recorded on the public ledger and synchronized across the network.

Unlike Ethereum, the camps of Bitcoin Core and Ethereum Classic – the "code is law" crowd, consider the immutability of the canonical ledger and the consistency of the core protocol to be inviolable first principles from which the value and usefulness of the system fundamentally derive. As such, the DAO fork that split the chain in two in order to reverse the hack is considered to have been a violation of the immutability principle by some and a case of intervention under circumstances critical enough to constitute a “state of exception”, a potential existential risk, by others.

On the other hand, unleashing a peer-to-peer cryptonetwork running a protocol religiously maintained by a "code is law" philosophy of governance, which by definition excludes the possibility for any discussion on the matter, may be interpreted as an attempt to facilitate activities otherwise prohibited by law or considered illegal, subsequently inviting all kinds of anti-social behaviors.

It should not be surprising, but a crypto legal system operating on principles as anti-legal as Szabo’s law will naturally eventually become illegal. As a result, Szabo’s law is in conflict with Crypto Law #2.

And since I tend to be very fond of etymology, I can’t help it but point out the Greek origins of the word “idiot”:

idiot (n.)

from Greek idiotes “layman, person lacking professional skill” (opposed to writer, soldier, skilled workman), literally “private person” (as opposed to one taking part in public affairs), used patronizingly for “ignorant person,” from idios”one’s own”

Vlad has always taken a more socially involved and less formal view of how blockchain governance should take place and considers it the “most important factor that will determine whether blockchains end up being a public good, or a menace to the public.” So, it shouldn’t come as a surprise when he calls for abandoning the doctrine of what he terms as Szabo’s law, as rooted in a particular political ideology, despite claiming to be apolitical and objective.

We need to abandon Szabo’s law to adopt a more open and secure legal posture. One that acknowledges rather than shrugs off its responsibility to carefully manage disputes. One that does not write crypto law to push politically unpopular outcomes on society.

Because I cannot help myself. Remember the doomsday machine from Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove? Yet, we’re expected to blindly put our trust in a group of people who were just learning first-hand, over the past decade, why financial regulation exists in the first place, or as David Gerard eloquently put it: “As a financial instrument born without regulation, Bitcoin quickly turned into an iterative exploration of precisely why each financial regulation exists. A “trustless” system attracts the sort of people who just can’t be trusted.

We’re prone to mistakes and miscalculations, especially when entering uncharted territories (and we’re talking experimental peer-to-peer crypto-economies and globally distributed coordination on the basis of shared record-keeping following the rules of a protocol, etc., so we musn’t forget just how fragile and early phase things are still). So, it is not so much a matter of ultimately trying to prevent making mistakes or avoiding them by all means (that would also arrest our development and capacity to learn from mistakes, as well as knowing how to adequately deal with them), but rather find ways to minimize and contain unwanted consequences, preventing them from spreading and escalating into systemic failures and existential risks (i.e., eliminating single points of failure by distributing them, one of the design rationales of shared ledgers as record-keeping and public accountability mechanisms). Zamfir puts it as follows:

We cannot foresee the nature of all of the blockchain governance disputes that will arise in the future, and need to retain the ability to remain flexible enough to adapt to changing circumstances, we cannot afford to blindly pledge our fates to a future with autonomous software.

The statement concludes:

His attempt to create autonomous software that is above any (other) law must be foiled by law people who are able to see through Nick’s bogus legal theories.

But we must stand in awe of the astonishing success of Nick Szabo’s law, and of Nick’s evident ability to tap into the distrust that permeates the modern legal and political climate.

And we must pay due tribute to the legal and political climate that legalized Szabo’s law.

Since mentioning ANT along the lines of technology, governance, and politics, I find this short eight-minute talk by Grant Kien below especially relevant and insightful in relation to the subject at hand. Kien is a digital media and cultural critical studies (qualitative research methods) researcher that is largely influenced by Latour’s Actor-Network Theory

It is even worthwhile to transcribe some of the above:

So, when it comes to politics, machines are very good political alllies. Their immutability makes them really good at keeping other allies in place. They become part of the political order of the world and their inertia (there’s a lack of opposition to them) makes the dominating actor look stable.

Think about a military apparatus, the inter-continental ballistic missle system exists and doesn’t change eventhough the actors in the network do change. It stabilizes a set of relationships that are needed to both control and maintain that particular armament, so it makes a very stable ally in that sense.

And authority figures that are people work as part of the administrative machinery. They resist individuation in the practice of translation, so they come to occupy a role within the appratus and in doing that they resist becoming somehow unique. They administrate the translation of any script from one repertoire to a more durable one and their role is very similar to any other machine in that sense.

And considering the above, Zamfir is also right to point out that Szabo’s law (or his notion of how crypto law should be instituted and carried out) is, on the contrary (though it is politically uninvolved or pragmatically apolitical), very much politically loaded and possibly so motivated. Let’s just recall how open air mining rigs had been reported to interfere with the LTE frequency spectrum. While somebody somewhere thinks that weaponizing autonomous drones is a good idea. There’s all the ways in which things could go terribly wrong by introducing more autonomy and, in the end, perhaps little value in the martyrdom of stubbornly insisting on the canonical immutability of an obvious mistake.

“Governance in Web2 vs. Governance in Web3”, a talk Vlad Zamfir gave at the Web3 Summit in 2018.

Nonetheless, an important distinction must be made between two different regimes of operation. Daniel Kahneman, a Nobel Prize laureate from the Jerusalem University known for his work in behavioral economics and the psychology of judgment and decision-making, posits in his “Thinking, Fast and Slow” that a dichotomy between two regimes of how the brain forms thought exists. One is fast, automatic, stereotypic and enabled under critical circumstances of emergency or an immediate threat. The other is a modus operandi of slow, deliberate, conscious and logical-analytical type of reasoning that takes place under the normal circumstances of a secure environment and no imminent, impending threats. The fast regime automatically activates a different network of associations alight, the fight-or-flight reflex if you will – where thinking only slows one down to do what is necessary in the immediate moment.

The fact that the dictatorship is originally considered to be an invention of the Roman Republic, a political instrument invoked under special circumstances where an extraordinary magistrate was nominated for a period of time to dissolve a dangerous situation by whatever means considered necessary and usually resigning before the official time to step down, whenever the objective of his task had been accomplished is noteworthy. It could be said exemplifies the above in the context of governance and law – a shift from the usual, commonplace parliamentary democracy (for example) to sudden emergency mode “state of exception” where decisions need be taken and executed fast, unhindered by the usual (democratic) political processes.

Which of the above components should be delegated to autonomous machine-driven machanisms and to what extent or scale remains an open question, but in any case it should be pointed out that libertarians seem to often forget why the polity of the state exists in the first place – precisely so it can provision such emergency mechanisms that trigger rapid mobilization in response to some threat or another whenever needed. In “Formalizing and Securing Relationships in Public Networks” Szabo points out that “if we started from scratch, using reason and experience, it could take many centuries to redevelop sophisticated ideas like contract law and property rights that make the modern market work.”

But the digital revolution challenges us to develop new institutions in a much shorter period of time. By extracting from our current laws, procedures, and theories those principles which remain applicable in cyberspace, we can retain much of this deep tradition, and greatly shorten the time needed to develop useful digital institutions.

And there is much truth in that, since evolution – whether biological or cultural, operates more so by repurposing the function of existing structures, than by inventing and evolving new ones. And technology being value-agnostic, it expresses decisions for users according to the tasks it is put to and programmed to perform.

None of us see the system. We see our own part based on our own background and history. And we all think we see the most crucial part.

– Peter Senge, Accelerate 2014

Augur, for instance, is inspired by Hayek’s vision of market price mechanisms as efficiently absorbing of available information and thereby relaying authentic economic signals that coordinate economic activity at scale. For such an economy, however, decentralization and censorship resistance are necessary preconditions. A critical mass of sufficiently distributed user bases is another, but that user base also needs to be technologically literate and fairly well educated (because “we see what we know”) to be aware of and understand the implications of their interactions.

This is part one of a two-part piece on “Szabo’s law” and competing notions of the sovereignty of code in decentralized governance models. Part two will appear on March 16th.